Interest rates peaking as inflation moderates in the US

Turn neutral government bonds and duration, while reducing underweight in equities. Maintain modest overweight in commodities to hedge against unexpected inflation

Nowhere to hide this year except in cash and commodities: I have been recommending a strong underweight position in equities and bonds, an overweight in commodities and cash since 4Q2021, together with a small position in gold since 1Q2022 (see links here and here). These in turn reflected my macro views that central banks will raise interest rates aggressively to combat persistent inflation, significant supply-side constraints in commodity markets, coupled with an economic slowdown in Europe and China. My views have generally worked out well, with the key exception of gold, which has been weighed down by rising real rates (see Chart 1 below for performance of key assets).

Chart 1: Commodities and cash have outperformed since 4Q2021, while equities and bonds have been hit hard. Gold weighed down by rising real rates

Source: Yahoo Finance, based on prices adjusted for dividends

Macro drivers are changing - US inflation is likely to slow more than many analysts are expecting next year: Moving forward, some of the key macro drivers of markets mentioned above could look quite different as we head into 2023. In particular, I believe US inflation will moderate more than many in the market are expecting over the next 12 months. This is notwithstanding a continued rise in the shelter component of inflation, as the lagged impact of higher rentals feeds into the Consumer Price Index.

I highlight four key reasons why US inflation should slow meaningfully:

First, some of the idiosyncratic components of US CPI such as medical insurance and leased car services will likely moderate from here. These two metrics alone could shave off around 10bps from sequential core CPI inflation. In particular, the Bureau of Labour Statistics will update the medical insurance index with new data on retained earnings from insurers over the next 12 months, which will likely show declines over time. In addition, the leased car services index has suffered from significant data collection issues and has been a source of volatility to CPI in recent months (see Chart 2 below). Recent price spikes in the leased car services index are unlikely to continue into next year (see links here and here for an analysis).

Chart 2: The Leased Cars Services Index spiked in recent months, contributing to volatility in the CPI. This is unlikely to continue into 2023

Second, core goods inflation should decelerate further, reflecting healing supply chains, elevated inventories, lower commodity prices, coupled with lower pass-through to import prices from a stronger US Dollar. The most prominent example is perhaps used car prices, which have surged more than 50% since 2020 at its peak, and will likely contribute meaningfully to disinflation moving forward, even if prices do not revert fully to pre-pandemic levels (see Charts 3 and 4 below).

Chart 3: Used cars CPI should decelerate further in the coming months

Chart 4: The improvement in supply chains and moderation in freight rates should help lower core goods inflation as we head into 2023

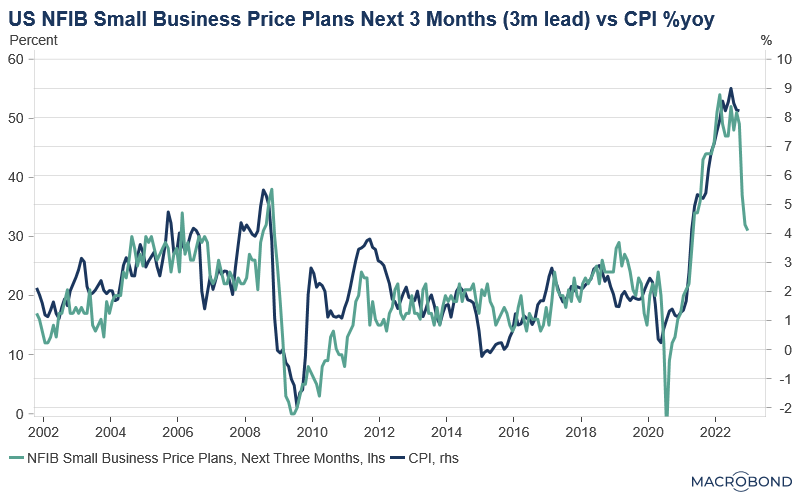

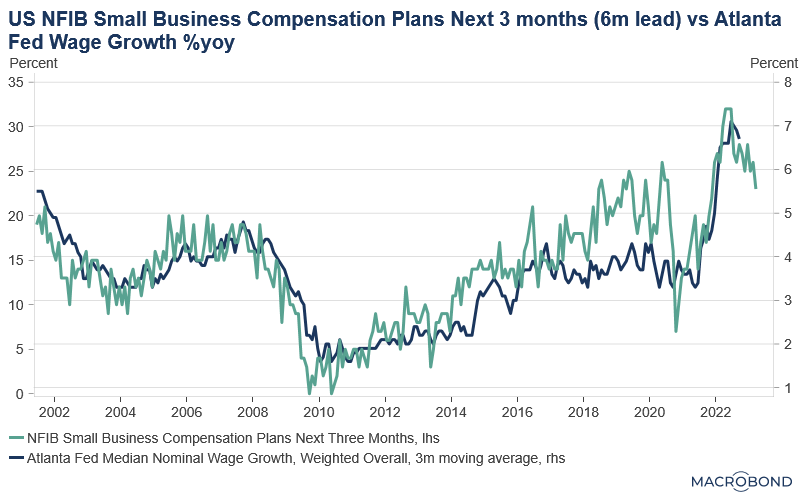

Third, lead indicators point to slowing demand and lower price pressures over the next 3-6 months. These include the ISM Manufacturing Prices Paid Index, the NFIB small business index, freight rates and supplier delivery times (see Chart 5 below). The labour market, which is typically a lagging indicator in the business cycle, is also showing some preliminary signs of softening with a decline in job openings, quit rates, and a slight moderation in wage growth. While average housing rentals are still rising, new rental contracts are already seeing some downshift (see link and Chart 6 below). This should portend a stronger disinflationary force in shelter inflation in 2024. Overall, my expectation is that lead indicators will continue to shift down over the next few months, providing clearer evidence of a growth and inflation slowdown in the US.

Chart 5: Lead indicators point to lower price pressures, together with some initial signs of softening wage growth over the next 3-6 months

Chart 6: While average effective rents are still rising, new rental contracts are starting to come off from high levels

Source: Cleveland Fed and BLS - Disentangling Rent Index Differences (link)

Fourth, the lagged impact of tighter financial conditions and higher interest rates on inflation will become more apparent in 1H2023. Some of the more rigorous academic studies show that tighter US monetary policy takes around 3-4 quarters to feed through to the real economy and inflation (see link to an example and Chart 7 below). Hence the peak impact to inflation from the policy tightening thus far should be far more pronounced in 2023 rather than this year.

Chart 7: Monetary policy shock impacts CPI with a lag of around 3-4 quarters

Source: Bu, Chunya, John Rogers and Wenbin Wu (2019) (link)

The Fed could have the policy space to pause rate hikes in a durable way in 2023. Any recession likely to be mild due to strong balance sheets: With core and underlying inflation likely to slow in a sustainable fashion as we head into 2023 for reasons mentioned above, I see the Fed having the space to hold rates at a restrictive level at slightly under 5% through 2023. Fed officials have started to talk about slowing down the pace of tightening, with a view to ultimately pause in 2023. This also allows the Fed to maintain the optionality to shift policy in a more data-dependent way over next year. Any potential recession will likely be mild, given strong balance sheets of households, corporations, and financial institutions in this cycle.

Where I could be wrong - Commodity prices is a key uncertainty: My implicit assumption is that commodity prices will remain subdued around current levels as global demand slows, outweighing the structurally tight inventory and supply situation of many commodities. Nonetheless, there is certainly some risk that commodity prices could rebound again if there is another supply-shock. The recent pick up in diesel prices in the US east coast due to low inventories is one key example of a risk to watch out for (see Chart 8 below). Nonetheless, China's lengthy delay towards removing its zero-Covid policy should go some way to removing upside risk to global commodity prices, coupled with weaker global demand overall.

Chart 8: Inventories of distillates such as diesel are at their lowest since 2008

Shift to neutral on government bonds and duration, while reducing underweight in equities. With rates likely to peak soon but remain high for longer, we recommend shifting to a neutral view on government bonds and duration, from a strong underweight previously. Meanwhile, with many investors already positioned massively short Equities right now, we think it may be worth paring back our bearish positioning on risk assets. I fund these changes through a reduction in overweight to commodities and cash, together with removing my position in gold. I recommend staying underweight in credit overall for now to guard against rising default risks and credit spreads. Meanwhile, maintain a modest overweight to commodities to hedge against inflation risks, albeit a smaller position than what I had before.

Turn neutral on the US Dollar. We have been positive on the US Dollar since June 2021 (see link here and here). We now turn neutral on the US Dollar as the Fed is likely to turn less hawkish through 2023, assuming we are right that US inflation risks are abating. Nonetheless, we do not think it is time yet to turn outright bearish on the US Dollar yet, given the uncertainty surrounding the magnitude and severity of a global recession.

Structurally higher interest rate environment - the era of cheap money is gone: It’s important to stress that I’m not calling for a return to the pre-pandemic era of low and manageable inflation. Rather, my view is for a cyclical downturn in price pressures due to the impact of tighter policy settings. My best guess right now is that inflation will be structurally more volatile in the decade ahead, reflecting a supply-side which has become more inelastic and less responsive driven by megatrends such as decarbonisation, climate change, and deglobalisation. As such, we are unlikely to return to the pre-pandemic era of low interest rates and cheap money.